In 2008 Printmakers Council took part in a discussion at the Fine Art Trade Guild to identify common standards that might be applicable to both the original artist’s print and the giclee reproduction print. Artists representing both groups were present and we were told that any agreed statements would be taken by the Fine Art Trade Guild to the British Standards Institute with a view to devising a BSI standard for the fine art print. This at any rate was my understanding at the time. I was there to represent our then Chair Sheila Sloss who at the time was unable to attend.

In 2008 Printmakers Council took part in a discussion at the Fine Art Trade Guild to identify common standards that might be applicable to both the original artist’s print and the giclee reproduction print. Artists representing both groups were present and we were told that any agreed statements would be taken by the Fine Art Trade Guild to the British Standards Institute with a view to devising a BSI standard for the fine art print. This at any rate was my understanding at the time. I was there to represent our then Chair Sheila Sloss who at the time was unable to attend.

The discussion turned on the basic question ‘what is a print?’ The artist printmakers were unanimous in agreeing that a print was a work of art designed and made as a print, by the artist, and not a reproduction of an existing work of art. This was radically different from the view taken by the giclee printers whose belief was that anything that could be copied and printed was inevitably a print. In addition, they were also unanimous in asserting that such prints could be signed by the artist and printed and sold in limited editions.

Since that meeting it has transpired that a BSI standard already existed and was produced some time during the 1980s or early 1990s. Seemingly, none of us were aware in 2008 of BS 7876:1996. To my recollection it was not mentioned, and it was not discussed. Although PmC had been one of the contributors to the writing of the standard no one on the PmC committee at the time seemed to know of its existence. The reason for this ignorance was perhaps due to the fact that in the late 1980s or early 1990s a large amount of PmC paper records were destroyed, a fact that came to light when our archive was being prepared in 2015 ready for deposition in the V&A.

Officially the standard is withdrawn. That does not mean that it isn’t useful or can’t be used but simply that there is currently no committee in place to oversee its continuing relevance to printmakers. It is officially categorised as ‘no longer relevant’. Currently there is some interest in reforming the committee and reviewing the standard, and PmC will of course seek to be represented. The standard may still be used but like all standards it depends on a common acceptance, on printmakers, publishers and galleries being prepared to use it, which may be another reason why it has been withdrawn.

A preview download of the standard is available on the website and a summary of its main points is set out below. The full download is only available to BSI members or to the public at a cost of £110.

The standard defines seven different types of printed material.

- Category A

‘A’ denotes that the artist alone created the matrix and made impressions from it. The inclusion of a print in this category implies the artist’s total and singular involvement.

- Category B

‘B’ denotes that the artist alone has made the matrix and a collaborator, or collaborators, made impressions from it.

3.2.3. Category C

‘C’ denotes that the artist made the matrix with the help of a collaborator and that a collaborator or collaborators made the impressions from it.

3.2.4. Category D

‘D’ denotes that the artist neither prepared the matrix nor pulled the impressions. Collaborators did the physical labour, but all the activities were carried out with the artist’s supervision and permission.

3.2.5. Category E

‘E’ denotes that the artist or artists agent has authorised the making of a print from a pre-existing image, but has had no further involvement with it.

3.2.6. Category F

‘F’ denotes that the print has been made without the permission of the artist or the artist’s agent. Inclusion in this category implies no involvement on the part of the artist, either practical or sympathetic.

3.2.7 Category G

‘G’ denotes that the matrix used for a print in categories A to C is reprinted without the artists knowledge or permission (see A.6 and A.7 respectively).

A.6. refers to ‘restrikes’ from pre-existing plates and A.7. refers to continuing to print from matrices made for unlimited printing. In addition, the Standard sets out various appendices explaining terms and variables.

We can see how these categories can perhaps relate to prints as usually made, covering solo artist printmakers (A), those who work with editioners and/or studio assistants (B and C), reproduction printmakers (D), publishers (E), and perhaps even copyright infringers (F and G).

‘hand-drawn and hand-printed or mere reproduction . . .’

But just what is a print? One of the difficulties in any discussion of this kind is that, in English at least, the same word is used for an original artist’s print and a reproduction; they are all ‘prints’. In practice the print is further qualified by saying ‘original print’ or ‘artists print’ or ‘giclee’ print. At the 2008 meeting Printmakers Council proposed that a way forward might be found if the makers of reproduction prints agreed to describe their products as ‘reproduction prints’ to distinguish them from ‘original prints’. This proposal was not accepted, and the meeting ended in inevitable disagreement.

The problem has occupied Printmakers Council since its inception. One of the founding objectives for PmC was to gain recognition and status for contemporary printmaking. Rothenstein and others like him argued that existing print societies were at the time too conservative, and the few print archives that did exist excluded the contemporary printmaker. They were keen to promote contemporary printmaking. Their work may now seem quite conventional but back in the 1960’s many of them were at the forefront of contemporary practice, and this included innovations in print process as well. Screen-printing, which had been in use for many years as a commercial process was then being introduced into fine art printmaking, largely in response to its use by Pop Art painters and printmakers. It is now difficult to believe that screen printing at that time was regarded in some quarters as not quite acceptable. A similar situation pertained later regarding photo etching, initially unacceptable but nowadays common place and unremarkable. To these we might now add digital printmaking and even cyanotype. In each case the central issue seems to be about photographic reproduction. If printmaking is simply a question of taking a photograph and reproducing the image photographically onto a plate or screen, then surely it is nothing more than a reproduction of a photograph? This much seems incontrovertible but what we must remember is that was seldom the case with either method. Photo screen-printing and photo intaglio prints have always involved some form of image manipulation, either in the printing or in the photograph, the most obvious example of this is the work of Andy Warhol. Whether you regard them as paintings or prints, and that itself can be a further cause for debate, there is usually some manipulation of the photographic image, either by superimposing blocks of strong colour or only half printing the screen, or some other intervention. That may never have satisfied traditionalists who maintained, and still maintain, that printmaking is mere reproduction unless it involves a hand-drawn as well as hand-printed image.

Screen printing and photo intaglio began life as commercial processes and this migration, of commercial print processes into the world of fine art, has always happened and has often met with resistance from those keen to preserve the traditional status quo. We should not disparage this resistance too much. If traditional methods and traditional views continue to serve the purpose of artistic expression, then they are far more than just a blind conservatism. But at the same time art thrives on change and innovation. The Pulitzer Prize winning American art critic Jerry Saltz, no stranger to controversy himself, has written recently and approvingly, of how art has always been made by the mavericks, the ne’er do wells, the outsiders, the ones who break the rules. (Saltz, 2020) He was writing on the Covid-19 pandemic and its restrictions and the effect on the art world, and as a consequence forecasting the death of the top heavy corporate art world and its bloated art fairs, but at the same time predicting the continuing health and vitality of art itself, because of the mavericks who make it. In short, art is not bound by rules or conventions or traditions nor in truth governed by corporate money.

Let us return to the ‘giclee’ printers and the problems they are causing. First, we need to qualify the term ‘giclee’ which by itself is unhelpful and confusing, although it is a handy piece of shorthand. A giclee print is simply a digital photographic inkjet print.

The problem can be set out quite simply. Giclee printing entails making a high definition digital scan or photograph of an original piece of work and printing it digitally to the highest possible technical and material standards. The print run can be virtually unlimited although in practice a limited edition is usually declared. This helps to give the print a certain cache and status, perhaps increasing the price and desirability of the work, although in practice such prints are relatively inexpensive. It’s a common process, most major galleries produce ‘prints’ usually described as ‘art prints ‘of works in their collection, and a very wide range of similar works are available from many other online and real-world retailers. Little image manipulation is involved. The most that is done is to compare and adjust the colours of the digital file to as near those of the original as possible.

The fact that giclee reproductions are sold as limited-edition prints requires passing comment. The concept of the limited edition is a nineteenth or twentieth century innovation, introduced to preserve the price and authenticity of any multiple. It was adopted in the nineteenth and twentieth century as a way of securing the integrity of the print and the price of each one. It is nothing more than a commercial convenience that can be, and is, applied to a whole range of consumer desirables. Printmakers do not have a monopoly on the term: you can buy everything from luxury cars to commemorative porcelain in limited editions. Often enough the declared edition can have a very large limit making it, to all intents and purposes, virtually unlimited. This ensures that a lower unit price can be asked for the product, thus potentially maximising profit margins, or conversely small editions may increase the unit price and resale value of work by leading artists. These considerations may be important for all printmakers as income or partial incomes are potentially at stake.

Warhol of course did not make digital prints, but I feel sure he would have done so had he lived long enough. He is reported to have observed that he could safely let his printer just get on with it as he did not need to get involved himself. This of course was perhaps mere talk, but it represents not just Warhol’s love of irony and hyperbole but also the central characteristic of his work located in the anonymous, the mechanical and the superficial aspects of the modern industrial world.

There are still printmakers who regard processes that are open to photographic manipulation as somehow less legitimate. Some evidence of human intervention, ‘the maker’s hand’, is for them required. It is after all for many printmakers one of the things that attracted them to the medium in the first place, that sense of involvement with craft practice, and the alchemy of process. But this in my view cannot be and should not be an exclusive position and certainly not for an open print society like Printmakers Council. Although PmC has consistently upheld the belief that an original print is made intentionally as a print and that the matrixes are by the artist, our founding members as noted above were keen to promote and champion the contemporary print.

The contemporary in printmaking is not something set in stone; developing technology alone will ensure that processes will change. Students and younger printmakers will bring and are bringing fresh ideas about what a print might be, and this together with changing ideas about the nature of art itself means that tomorrow will not look like yesterday. I believe that it is time to re-draw our parameters; to really become an open and diverse community that is not afraid of innovation, not stuck in its ways, not functioning like a preservation society but fully embracing the contemporary ideals of our founders as with others we take printmaking on into the twenty-first century. Anything else will ensure that we become nothing more than a quaint irrelevance.

And it is at this point that I return to BS 7876:1996 for here we have a blueprint for how we might finally resolve the perennial discussion over the definition of a print, original or otherwise. Despite being currently discontinued, a status which I believe is open to change, the standard embraces all conceivable ways and intentions for making prints. As inevitable change continues it may be adapted, re-written, extended, in ways presently unknowable. But it allows artists, collectors, galleries, academics, and exhibition organisers to know exactly what they have in from of them. It is a most useful document although it will only be any good if people use it.

‘an open, diverse, print-promoting organisation’.

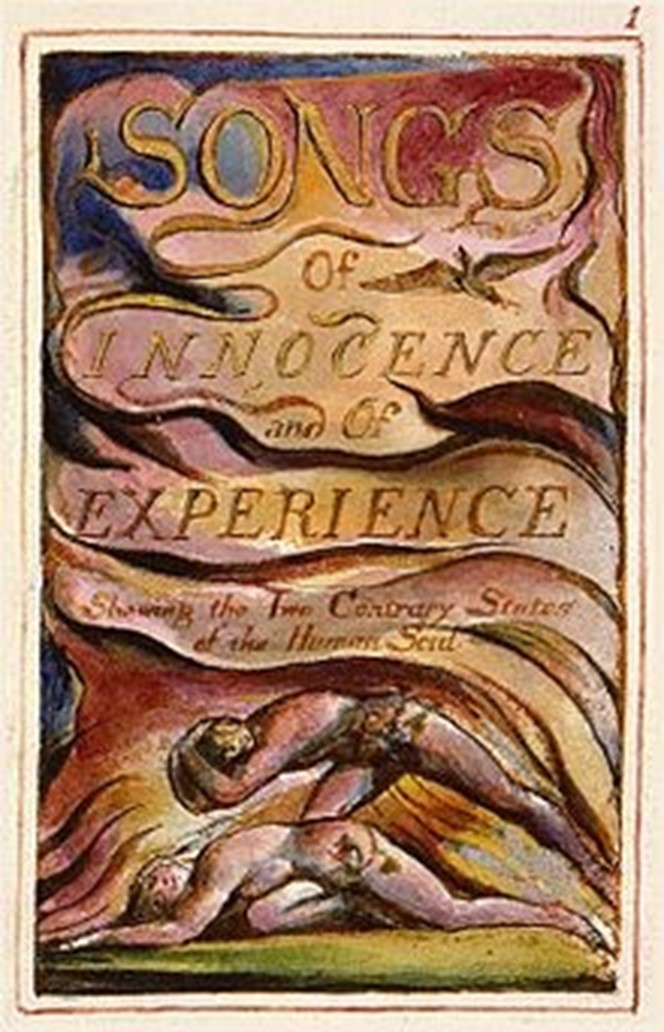

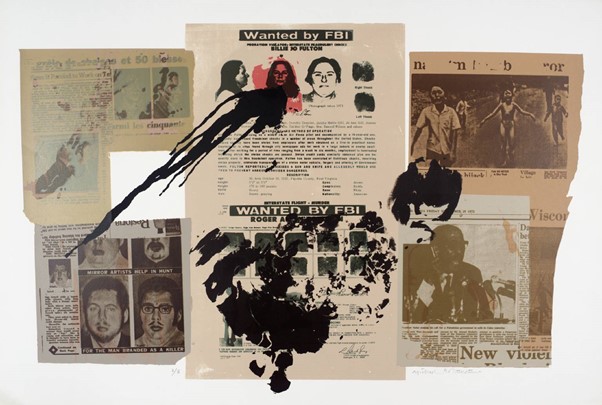

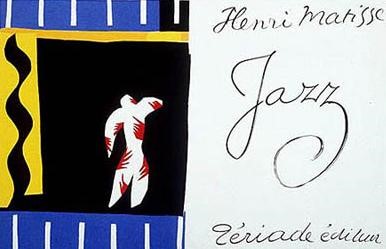

Many of the great artist printmakers were innovators, forging ahead with prints that for their time were unconventional and challenging. From Rembrandt adding extra ink to his etchings, painting in effect, to William Blake’s relief printed and hand coloured ‘infernal methods’ of his ‘Prophetic Books’; to Michael Rothenstein developing open block relief printing from found objects coupled with half tone photographic plates and experimenting with woodcut and screen-printing combined, to Richard Hamilton’s late digital works, the history of printmaking is full of innovations. In the 1940s Matisse made a series of cut outs for the publication Jazz. The cut outs were reproduced as stencil prints and the book, published by Tériade, is now regarded as one of the artist’s masterpieces. But Matisse was dissatisfied with the result later confiding that he did not like it because the stencils did not reproduce the three-dimensional qualities of the cut and pasted collage. Today those cut outs could be reproduced more easily using giclee printing, which might also preserve some semblance of the surface qualities. It is impossible to know of course but one cannot help wondering if Matisse might have been happier with this. Later, the artist did authorise a series of lithographs made after the cut-outs but died before the project could be completed.

Innovations in printmaking have most commonly taken the form of technical innovations, in which previously and exclusively commercial processes have been adopted by the fine art world. This continues, and with the advent of a digital world it has brought the problem of print definition again to urgent consideration and again provides an opportunity for printmakers as a community to reflect on what and who they are as artists.

Grayson Perry has recently written about his early work in ceramics. (Perry, 2020) Looking back he said, ‘I did not want to settle down on the craft side . . . I did not want to be defined by my medium’. He was ‘acutely aware of a class divide’ between himself and craft potters and ‘learnt that defining myself as an artist was important’. I think it can be fairly argued that in being dogmatic about the precise nature of the original artists prints, and quite sure about what is excluded, we are allowing ourselves to be defined by the perceived medium of print. There is of course nothing intrinsically wrong with this, it may be right for some people, but I believe it carries with it certain constraints and may prevent or hinder innovation and the pursuit of the unconventional in printmaking. Printmakers may choose to be defined by the medium, or they can think outside the perceived boundaries in search of innovation and the unconventional. Just what this means in practice may include using anything from unconventional substrates and processes to, yes, giclee, 3D printing, and anything and everything else.

I have argued here that the existence of a BSI print standard provides a way forward largely because it is so comprehensive – we can be clear about an original print as compared to a reproduction print, simply by reference to the corresponding category or categories of the standard that apply to the work in question. But I have gone further by suggesting that innovation and change, and indeed breaking the perceived rules is the stuff of contemporary art in any period. For this reason digital printmaking should not be an issue; in fact I am surprised to be writing those words as I had believed up until now that that battle was over. We must recognise that it is over; that artists and students have gone beyond the definitions and constraints of the past. If we refuse to do this, we condemn ourselves to parochialism and the status of a preservation society, an irrelevance. We should do so while championing BS 7876:1996 and playing a full part in its continual development to keep pace with the rate of change. Only in that way can we be an open, diverse, print-promoting organisation that maintains the traditional methods and processes of the past while embracing innovation and inevitable change.

Covid-19 has played havoc with everyone’s plans and schedules for 2020, and quite possibly for a good bit of 2021 as well. In September 2020 Printmakers Council were scheduled to hold their first ever Symposium at the Royal Overseas Club, London. This of course had to be postponed. Hopefully only until September 2021. The topic and title remain the same: ‘Relaxing the Line: the unconventional in printmaking’. I don’t wish through this article to anticipate what the invited speakers might have to say, but I do hope that ‘unconventional’ will embrace alternative approaches to print definitions and processes.

References

Kennedy, M. (2015) A Sixties Pressure Group, in ‘Making an Impression, Printmakers Council at 50’, Imprimata, Chessington.

Perry, G. (2020) ‘Grayson Perry: The Pre-Therapy Years’, Thames and Hudson.

Saltz, J. (2020) The Last Days of the Art World . . . , 2nd April, www.vulture.com

Illustrations

William Blake, ‘Songs of Innocence and of Experience’, combined title page, 1794, relief etching with hand colouring.

Michael Rothenstein, ‘Violence, 1’, second version, 1973-4, woodcut and screen-print.

Andy Warhol, ‘Electric Chair’, 1964, screen-print.

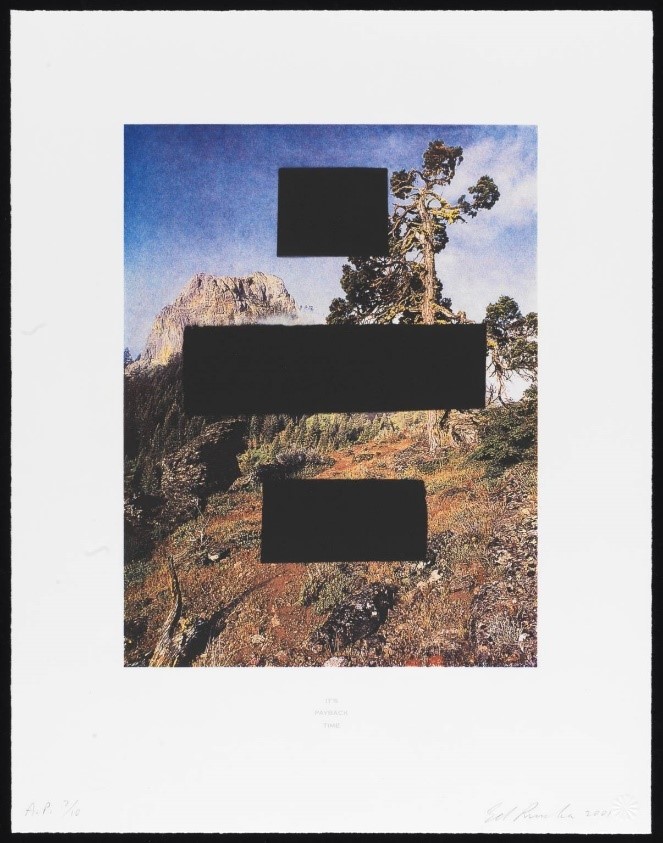

Ed Ruscha, ‘Its Pay Back Time’, 2001, photogravure.

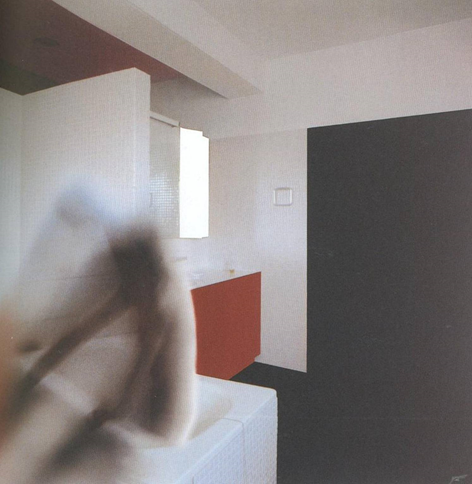

Richard Hamilton, ‘Bathroom-fig 1, 1997, digital print.

Henri Matisse, ‘Jazz’, cover of artist’s book 1947, stencil.

Gary Hume, Big Bird, 2011, digital ink print.

A brilliant and very informative essay, Michael. Thank you.

Thank you Angela.

Interesting read Michael. The older I get the more sanguine I become about the future of print and all its iterations.

Thank you Eric.

Thank you. Very interesting and informative. I shall keep this in my records.

Thank you Sue.

Great essay. As a print maker working with giclee printing (among other things) – these are definately issues that seem to get in the way! My personal print practice has evolved into giclee, purely because it is not achieavable any other way, an approach which I think is severely overlooked. I’m actually aiming at giclee printing as the mechanism to realise the images I want to produce. Incidently – part of the process I go through often involves scanning old screen prints into the computer, manipulating them and incorporating them into the final giclee print, again an overlooked and under realised process. An awful lot of multi-media work (including getting “inky fingers”) goes into a final image before the green “print” button is pressed. Does it matter if someone else presses the “print” button? I don’t think it does – at least not if it was me that asked them to press it! I also don’t think it matters if I get inky fingers, or not. It’s a bit like putting music onto an ipod that has originated from mp3, cd, vinyl, and even cassette – and there are no questions there as to whether it’s music or not………..?

There is considerable merit in your arguments and I am a traditional etcher but I also use whatever medium I think is relevant, but I do not produce limited edition giclee prints of photographed artworks.

Thank you Dan – good to have your comments and hear about your own practice.

Thank you Michael for this most informative, fascinating and superb essay. Truly brilliant!

Thank you Ros.

An excellent though provoking essay. I think it is getting harder to isolate the limited edition giclee print as artists increasingly deploy digital collage and screenbased art techniques that are then printed digitally by ink jet.

Yes many thanks indeed. Very interesting re. the BSI info. I think in North America they categorize prints more rigorously than we do and I have always thought we should follow suit so that, at least, buyers know exactly what they’re purchasing. I frequently get up on my soap box about the distinction between an original limited edition and a reproduction. So many people still don’t understand the difference. And I still hear galleries complaining about people saying they don’t buy prints because they think of the medium as inferior, often because they’re confused about the distinction. I also struggle when I attempt to communicate the idea of a digital print being an original – even some printmakers struggle with the idea – and, like you, I find this surprising because I thought the battle was over too. I, myself, am a traditional printmaker specialising in etching, but am passionate about the importance of keeping an open mind to all forms of change and innovation in printmaking, having always been aware and averse to the potential for parochialism that you mention. It seems strange to me that we should even have to mention it really! I choose to use etching to express my ideas but I’m definitely not defined by it. I very strongly agree that there should be a British Standard and look forward to resolving the constant debate over the definition of a print which has been going on as long as I can remember (and that is quite a long time now!!).

Thank you for your comments Mary – I think the debate will roll on for a bit longer!

Thank you so much Michael. Very interesting comments too.

I am going to print this on my inkjet printer, and use it as a handout for discussion in Printmaking classes. Further to that, it’s so good to have this on the PMC website, it opens up the debate, it is something to refer to when many people ask questions, I haven’t really had anywhere to send them.

What now will happen with the BSI print standard, can it be revived and added to? Thanks also to David Atherton who contacted us through the facebook page, and got the whole thing rolling again, is he involved?

This was really helpful, thank you. It pulled together a lot of thoughts I’ve had over the past years and how I have wrestled with my own ‘rule bound’ views. Having started printmaking in the early 1970’s I have grown through some of these changes in attitude and have shed many of my old views. I think the debate about the process and what is an original print is multi facetted and I feel that much of the problem ( for me ) is about honesty and the public being made fully aware of what they’re are buying. I have had numerous family/friends report buying a giclée print having thought that they have bought an original print and very upset to discover what they’ve actually bought.

Thank you Theresa. I don’t know about David’s involvement but he alerted us to the existence of the BSI, which in retrospect I should have perhaps made clear.

Thank you Theresa (Taylor) I do agree it’s about honesty. I don’t have any arguments against giclee prints or ‘art prints’ as they now seem to be called but passing them off as original works rather than reproductions is fundamentally dishonest. Giclee as a process is just that, a process like any other which we shouldn’t be reluctant to use.

Thank you Sarah, and thanks for your comments.