THE EVOLUTION OF TECHNOLOGY –

its impact on Printmaking and the Creative process.

Stephen Mumberson – Associate Professor in Fine Art at Middlesex University, London

PART ONE

Recently a full colour photo lithographic poster appeared pasted to street walls around the poorer parts of London. It was a simple image of a tower block from the seventies, a photograph taken from a high view point and clearly before local government decided to’ improve ‘blocks by adding cladding. Once the viewer realizes which tower block this image is, the meaning of this printed image is crystal clear. A simple printed poster image no doubt found on the web, unstated yet carrying a subtext that vibrates with the knowledge of future horrors. Printmaking clearly still has value in a digital dominated world.

Printmaking practice has been interwoven with technology from differing early historical routes to the broad different forms of the present day. Many printmakers appear to fear the new digitals means. The more conservative hark after a craft centred focus where the skilled hand and eye render the required imagery, while others gasp fully the potential of the new digital means both to extend and enhance their print practise. The fear of the digital appears to focus on the distance between the means to make the work and the physical materials used. These fears are familiar to printmakers trained in the 1970’s where the application of photomechanical processes created similar divisions and suspicions that printmaking was being eroded by technology. Few were aware at the time, that the micro electronic imaging and command systems developed in the post war period then used in the space exploration industry, automation and the military would parent the present digital world. The jump from photo or chemical reactions and physical rendering of materials for the creation of prints to the ‘abstracts ‘of the virtual electronic world carried out through printed circuits/software /operating systems, electronic storage through files, hard drives and operating through a central controlling device –the computer , has conceptually distanced the printers from the origins of the work. Unlike printmakers from the past, we can now originate, draw, organize, scan, overlay, scale, montage, enhance by software and process the basic data into a form that can be easily translated to printing plates or more complex forms via connected printers. Other than the monitor and the end results, the large number of calculations, the programme steps and data itself is the result of a series of encoded instructions carried out at speed. A multitude of binary switches whose multiple actions result in the required actions. Unlike the mechanical and hand rendered printing plates, stencils or stone surfaces of earlier print history process is carried out beyond physical stages,’ ghost ‘ like within a desk top machine with a back lit monitor which gives a coded version of the actions carried out within.

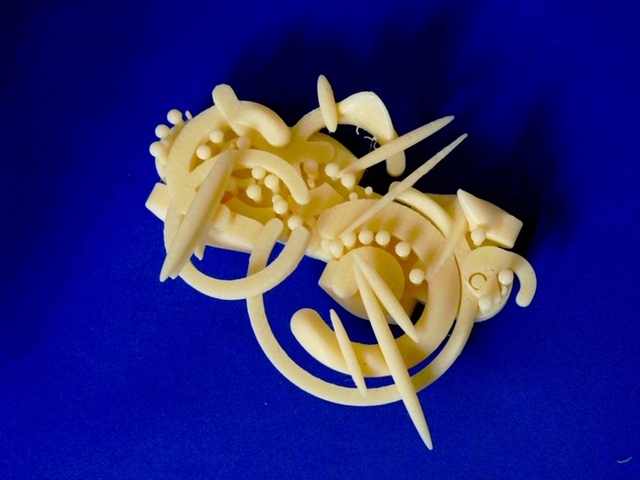

It would be a wrong impression to give that the modern printmaker merely transfers the digital moderated processed image/design to a plate and accepts the printed result as the completed work. Though this is possible most printers will reprocess data after a proof or alter, refine the plates to give the desired or fully created work. Much like a metal cast broken out of an investment block, the cast needs cleaning of feathering (surplus metal that has set in thin lines on the cast objects surfaces where the hot metal has found cracks in the mould), the

surface refined and chased, then either polished or coloured so the edition print

may go through several iterations, refined by proofing, colour trails, reworking of the plates by hand. Computer image processing rarely beats the human eye or judgement.

The digital revolution is a similar event to the introduction of the Jacquard Loom in France where fine textiles were woven using punch cards which carried operating instructions for the loom. The textiles produced were the equal of hand set /designed cloths and with further work could be programmed by punch cards to weave images or very fine patterns. It is the adaptability of the programmer, the imagination of the originator and then the purpose of the product produced that links the computer to this early 18th century loom. It is end purpose that printmakers should keep in mind with the new technologies.

The critical view of Printmaking is often focused on the formal abilities of print to reproduce, edit, make multiples, create graphic re-interruptions, to be somehow artificial, distanced from the unique. Print has been forever poisoned by the misuse of the ‘limited ‘edition which often is far from limited and often has little relation to the artists hand or engagement other than the signature on the paper. Sadly, the introduction to printmaking is becoming a rarer event in a art student life due to a growing belief that range of skills and abilities within studio practice are now subordinate to the concept and the theory. The days of the artist being able to carry out his or her concept fully may be coming to an end for these and many other economic reasons, not least concerning finding a studio space in most contemporary cities. The new technologies could offer a renewal and means to progress a new route for individual artist to progress their printmaking ambitions.

For those who fear the lost of direct physical engagement through our hands to materials it is a matter of choice. There is no inherent value in a new technological method within itself, any more than the matrix (material form of a relief block –lino, metal, wood or plastic) you use to make a relief print. It is the choice that gives the qualities and attributes you wish in that print work that could be simply a cut-out form using knife tools or a laser formed line in the surface of the block (or even both in combination). You choose the method, processes, process both manual or electronic to achieve that best expression desire or discovered through your individual work process.

Printmakers have walked through a transitional door way into a parallel but familiar world, where the print originator may be sited in a geographically distanced site anywhere across the face of the earth, and if he or she has an internet connection, send a file that could be uploaded by a distant operator to produce a print product or work through a laser cutter, large format printer and 3D printer which may be returned through the post or for exhibition in a gallery sited in a distant geographical place. This still is a little far off unless you are happy to gift work to the receiver or distant gallery. But in another world of international cartoon competitions, those competing from a distance often enter

a jpeg file to be printed out as a digital print at the distant site where the

competition is held. There are still many contests that demand the original drawing but it not uncommon to produce the drawing in a digital form, send it to the contest site, then printout as a A3 digital print –often in countries too distant or politically unstable to physical go to, or be sure that the post would arrive. I would not want to disagree with the printer who feels strongly that the traditional processes skilfully practiced have what can feel like a fundamental power and can uniquely express a deep human sense of the world that can feel ‘otherworldly’ almost beyond the manufacture of a mere human. But those works of genius were from times when gifted artists were allowed time to develop, change and refine a practice over a life time (if in good health and well funded then also escaping historical events of war or other disasters ).

But we as printers live in very different times. Where even time itself drives an assumption of production, places value in a fashion that would not be understood by our predecessors in pre-modern times. We are now bombarded by conflicted notions, ideas, politics, beliefs, scientific progression, imagery in all its available forms, information and knowledge of other cultures that would send the human mind of earlier historical period spinning. The pace of change seems to overwhelm even the best-informed mind, it may be seen as perverse not to use technology as a means both to express, but also try to capture these shifting rapid changes. There is the possibility that the new technologies in a short period in the near future will be seen as novel if not laughable or as distant from a future practice as the wax cylinder is now to a digital sound recorder. We as printers are left as adventurers in an expanding concept of printmaking that broadens its scope at a fearful pace. It is our shared human sensibilities that form the questions and valuations of these technologies, in the ever-changing streams of potential development within what we define as printmaking.

Most digital processes being adopted into the studio print practice have their origins in industrial manufacturing of market goods far distanced from the print studio. Large format printers started as banks of basic computer-controlled airbrushes assembled on a large x /y framework which could reach any point within the limits of the flat plane encompassed by the machine. These early machines produced adverts, image and text for the sides of vans and trucks and any large-scale text image combination. They were very limited by present day standards and the large pre-micro chip processor used to process and control the data from a basic scan. The cost was high and the permanence of the printed image poor. These fore runner machines father with the first desk top printers, the later development of large format printers whose range, scale and definition bear no relation to the prints of earlier machines. Large Format printers are considerably more capable machines than most common users put these printers to. There is a large area of potential adjustment and control within the machines themselves which does require an acquaintance with the controls that both control printer nozzle shape and the amount of the flow of the inks. But most large printers are set for a colour scale and print configuration that suits the printing of photographs. There is no reason why once more familiar with the soft war setting, that these printers cannot produce bright rich graphic colours. Again, these machines were never intended to be used to produce art work, though the interest and use by artists /printmakers has dictated their development. There are versions that print onto textiles, plastic surfaces and for durable use. The complexity, range of colours and resolution vary, the better machines producing high quality work at a cost. The quality of the inks is also important hence those using highly pigmented inks make more durable prints with a greater range of colour rendition but require high skill operation and the income to be able to work with the machines. The range of papers (which have a thin plastic layer-to aid the definition of the digital print) has grown greatly as has the similar progression of canvas qualities that can be used, there are a few high standard workshops in Holland and Germany that work to artist printmakers editioning standards. Digital printmaking still suffers from a characterization of being seen as merely reprographic or poor substitute for more noble printmaking arts. Costs, lack of expertise, the valuation and understanding of work produced, this holds back the full potential. It is a developing area needing a respectful practitioner and more open high skilled workshops to gain the status needed.

Stephen Mumberson. |